We don't weld, it's easier for us to lay up a carbon frame now.

Words by Dave Anderson, photos by Sim Mainey

Hope Technology are the archetypal bike industry success story – a company associated with no-nonsense components that just work, but that also manage to introduce a bit of colour thanks to the myriad anodised colours on offer. Bling is not a dirty word here. They’re a company that has seen a steady rate of expansion, and are now busy adding extensions to their fourth factory while planning an Olympic spec Velodrome on the site of the third. A factory packed with row upon row of CNC machines, intricately machining bike parts 24/7 that must surely now be familiar to most mountain bikers thanks to the number of times images and articles have been published featuring them.

Hope are also a refreshingly open company – unusual in an industry that thrives on non disclosures and future product secrecy. It’s typical that within half an hour of chatting over coffee we’d learnt that despite their first carbon frame still being at the end of the prototype stage, the second bike frame is already in development – the HB120, a 120mm travel 29er trail bike with the projected price tag of £6,500 for a full bike. That’s a competitive price point for a handmade in the UK carbon bike, but it fits well with Ian Weatherill’s ethos of ‘if we can make it in the UK, why not?’ that underlies everything Hope do.

So just where else are Hope headed? We settled down to chat new product lines, new directions, carbon production, and just what exactly they think the secret to the company’s success is with Hope’s ever friendly marketing department – Alan and Rachael.

Alan Weatherill – I’d like to think our success is because we do a good job of everything we do.

Rachael Walker – I also think it’s because we’re not that corporate, you talk to people when you’re out riding or you’re at shows and people can see the faces behind the brand. I think that’s what maybe sets us apart from some of the other brands, in some other brands people come and go quite quickly or shift between brands. With us lot they see us out riding and can see it’s a genuine love for riding rather than just something we’re trying to make money out of and maybe that kind of shines through and people appreciate that.

AW – You get all these Canadian brands that are ‘rider owned’, well we always have been so what’s so special about that? They make all these statements about rider owned – but you still don’t make the stuff do you? ‘No, but we’re rider owned though’.

We actually are rider owned, and we make stuff, and the guy down in the factory rides, and the guy who does the carbon rides – we all ride.

RW – If we have an idea in the morning we can have it online by the afternoon, you’ve got the freedom to do that. There’s only Alan to check with, and if he’s not around we just do it.

AW – We’re quite free-flowing.

RW – You just go with your gut instinct, I think you get a feel after you’ve been doing it a while of what works and what doesn’t. And if it doesn’t work it’s not the end of the world.

AW – We make products we want to use so they’re always made for a purpose. It’s like the bike – if it never sold it wouldn’t have failed because we’d have made some for ourselves. It all gets made, everything is done for a use.

RW – And if we make it because we want it it’s likely other people will want it too.

AW – Ultimately we’re too diverse really, as a company an accountant would look and say you’ve got too many products in too many areas, but if you look at rider surveys we’ll often appear in nearly every category and we’re always in the top few of every category. We might not be the best every time, but we’re always in there. Who else makes good lights, headsets, wheels, hubs, brakes and bottom brackets? We win on customer service because we do it how we want to be treated. That’s what it boils down to.

2016 saw the introduction of HopeTech Women rides, a series of events around the country that quickly gained a large following and spawned further regular women’s rides in the locations that they were held. We asked Rachael to talk through the background and reasoning behind them.

RW – The rides have been more popular than we ever thought they would be. It’s just under a year ago that we started it, it kind of came out of the fact that we just didn’t see that many women riding, or if you did they weren’t in groups but just with guys. I started thinking about the women who I knew who I rode with – Hannah Barnes and Katy Winton were all a two-hour drive away, I thought there must be loads of other women riders around here but you don’t see them or know who they are. All it needed was to arrange a meeting place and a ride that had a different purposes. One purpose was to get women meeting with other women who were already riding, another purpose was to start some instruction for people who were perhaps a bit scared to ride by themselves or didn’t feel confident riding in a group.

At races I’d done in America they had more social groups of women who ride together and I thought why does it happen out there and it doesn’t happen here? So the idea was to create an atmosphere, a bit of an arena to come to – split the rides into one that’s a bit more advanced and another that’s steady away and social. The first group can push each other, they can do it together without worrying about making a fool of themselves or someone criticising them. As we do more rides we keep hearing the same old thing in the stories women tell you. It’s a bit of a generalisation but basically it’s the partner who always tells them to hurry up or if they can’t do something to ‘just don’t touch your brakes’, which isn’t really that helpful. It’s not a male bashing thing, it’s just trying to create a place where you can get a bit more confidence.

It’s not anything revolutionary, we’ve just basically set up rides around the country and we’ve tried to do them midweek. I think it’s a good time to arrange them, to get out on a midweek night as a lot of people only ride at the weekends. The way we’ve approached it we don’t talk about Hope that much, I sort of felt when I’d been to other women’s events that it was pretty corporate, it was clearly for a purpose or a goal. It’s not the case if someone comes to one of our rides. It’s not that they’re not allowed to come if they’ve no Hope stuff on their bike, if we can just get a few more people riding or a few more riding more frequently and they love it as much as we do it’s got to be a good thing. If people want to talk to us about Hope we’re more than happy to but it’s not the focus or why we’re doing it. It’s just basically to get more bums on bikes. If we can get more people overall into bikes it’s got to be a good thing. Obviously we’d like to sell more stuff, but that’s not the motivation behind this.

Another common theme you hear a lot on our rides is that a lot of the women, if they were stuck in the wilds somewhere, wouldn’t be able to fix a puncture or put a new tube in – just basic things and basic things about looking after their bike. Again, it’s thing about worrying about looking a bit stupid or having to admit to not knowing how to fix something. So on our little courses we take between 15 and 20 women and spend the morning going through the anatomy of a bike. A lot of people don’t know what all the parts are called – we take it for granted working in the industry that they do, if you don’t know what those parts are, when you’re riding you might know what’s going wrong or doesn’t feel right but how do you describe it?

It’s about sharing knowledge so they can fix it, or at least give it a bit of a go. If you’re riding you should really know these things, you might not always be with someone who can fix things. We keep getting asked to do some advanced classes but at the moment we’re concentrating on the basics.

I know how awesome it is when I’m stood at the top of a mountain, I think it’d be great if everyone took a step out of the trail centre and rode a bit of natural stuff, that’s not to say it’s wrong if you don’t want to. We’re organising a women’s enduro race, but at the same time I don’t think everyone has to race , it’s just another option. It was just one of those conversations where you say wouldn’t it be cool to do this and seemed to natural for us to do it. Gisburn [forest trail centre] is just up the road, we’ve always had a bit of involvement in the trails, and most of our women’s rides are there. We’re a supporter of the PMBA [Pennine Mountain Bike Association] series, it’s on the same wavelength as we’re thinking enduro should be – mates getting together and going riding, a really good atmosphere and they’re quite friendly and welcoming. That’s what we want to be associated with. It’s just riding bikes at the end of the day, it’s not life or death is it?

If someone’s never entered a race before, women are quite different they can get more paranoid or worried about doing it, but if we can create something where they can just go and give it a go it can give them a taste of what it’s like to be in a timed environment that’s all good. If we get 50 entries, or 500 it’ll still go ahead – we’re investing in it quite a lot because it’d be cool to get a ton of women there having a laugh.

There’s no big master plan, there’s no big strategy, we just do everything by feel. If things are working then we’ll keep doing them and if they don’t we won’t. You’ve just got to not be afraid of failing. So if the race doesn’t go as well as we hoped it isn’t a disaster, it’s just one of those things.

Likewise, when the news that Hope were introducing the Hope Academy, a rental scheme for kids bikes that were light and blingy (as Ian Weatherill explains ‘if we can have bling bikes, why can’t kids too?’), it seems that the project was quickly oversubscribed.

RW – Ian’s big thing is that you always see kids riding crap bikes, or heavy bikes and when you think about it weight is a big thing – in relation to a kid’s weight the weight of some of the bikes is just totally out of proportion. The idea is we’ve got a couple of models of Earlyriders, smaller bikes, then some super-lightweight aluminium bikes with no suspension, apart from the 26” wheeled one which has suspension. They’re all just kitted out with decent components and rented out on a monthly basis. It’s a three-month minimum contract, but as your kid grows out of a bike you can just size up.

We’ve only shared information about it once, for one day, and we already don’t have any bikes left for a while. We’re trying to keep it on the low down but it’s not really working. Bikes and groupsets take a couple of months to get hold of, so it’s already a victim of its own success.

Running alongside that at each of the Scott Marathons we’ll be having a kids class. The marathons are always on the Sunday, but they have families there all weekend so we thought we’d give them something to do. We’ll be doing an hour and a half of coaching with the kids, there’ll be Paul Oldham, me, Alan, another guy from here and potentially some of the Scott guys. With four to six-year olds, and with seven to twelve-year olds we’ll be running skills sessions, getting a bit more confidence on bikes. That’s at each of the Scott Marathons, then this morning we decided during the school holidays, the summer holidays and May holidays, we’d do some day sessions at Broughton Hall because they’ve got a mountain bike course in there. It’s all totally free, but there’ll be limited places.

And then there’s the HB211, the prototype carbon bike that has had multiple press launches courtesy of the number of bike shows and trade shows it’s stolen the limelight at. A surprising move by a company associated with the production of components to move into making bikes too, though it turns out that the Hope branding that adorns the toptube of the HB211 isn’t going to make production.

Ian Weatherill – HB is the bike, Hope is the components. I think we’ll move the HB211 to the HB160, we’ll call it after the travel. And the next one, the HB120 – it seems the logical thing to do. The 211 is just the prototype.

AW – It’s obvious we’re going to do something else. It’s going to be a 130mm or 120mm 29er depending on who you talk to, a trail bike and it’ll have a carbon back-end. It’s back to this thing of ‘what do we ride?’

IW – It’s going to be a 120mm if it’s 29, it’d be 130 if it was 650b. Not too light. The enduro is great, it’s great in Whistler, it’s great in the Alps, but then you start riding around Gisburn Forest and it feels a bit over biked, so we’re working on the next one before we’re selling the first. We’re making it because we want it, most people here would ride that, it’ll suit Gisburn, The Dales, most places.

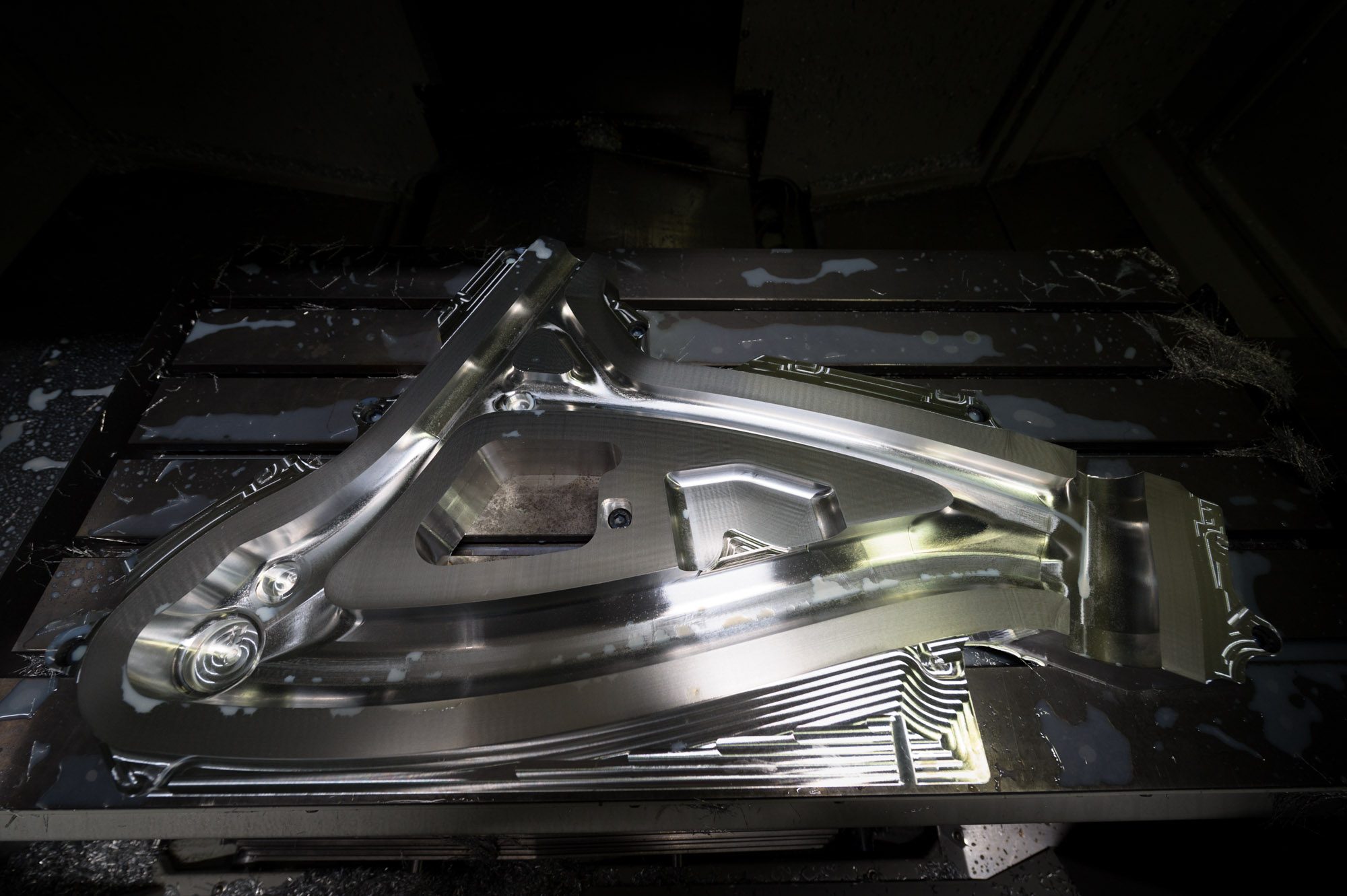

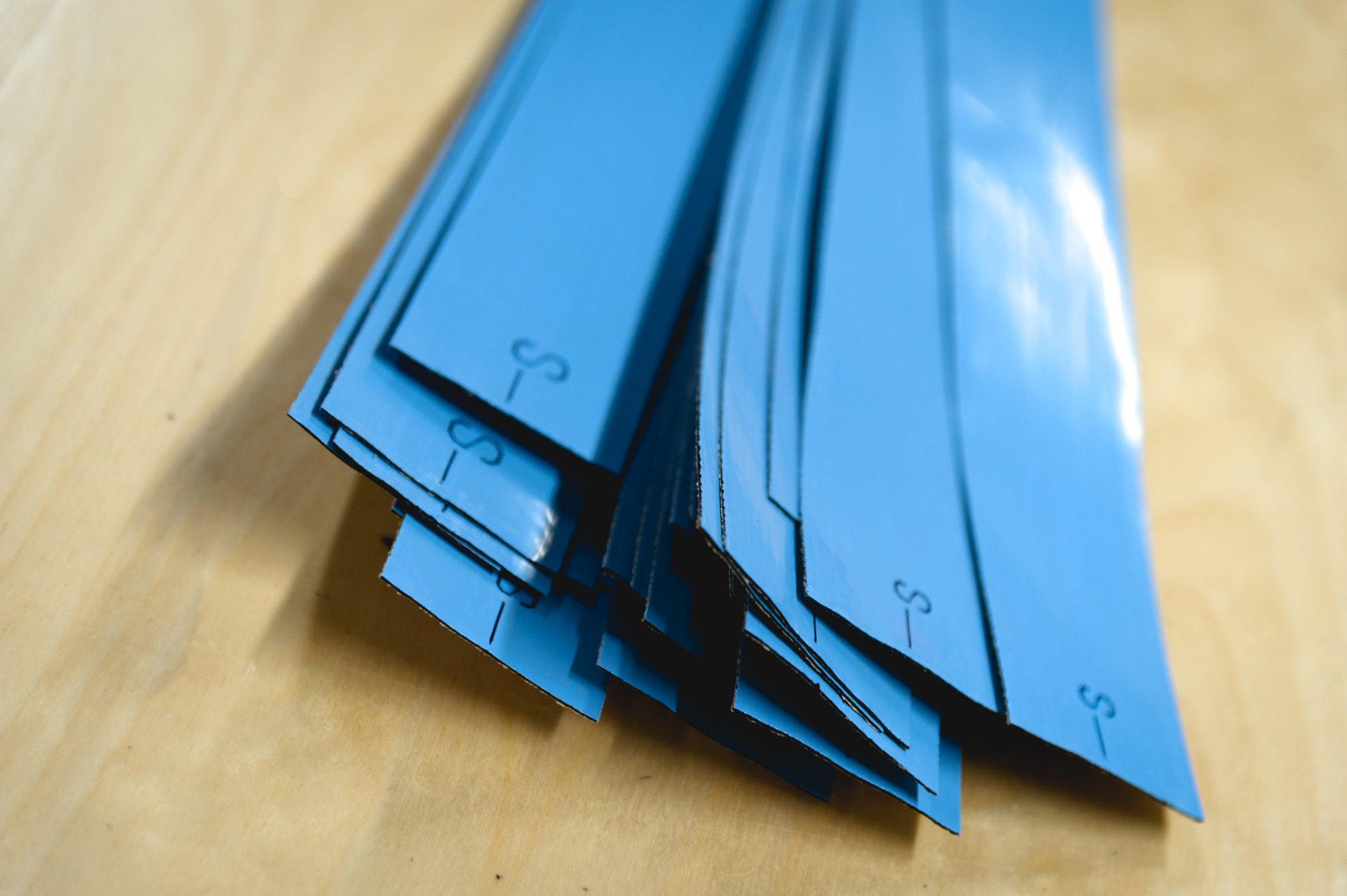

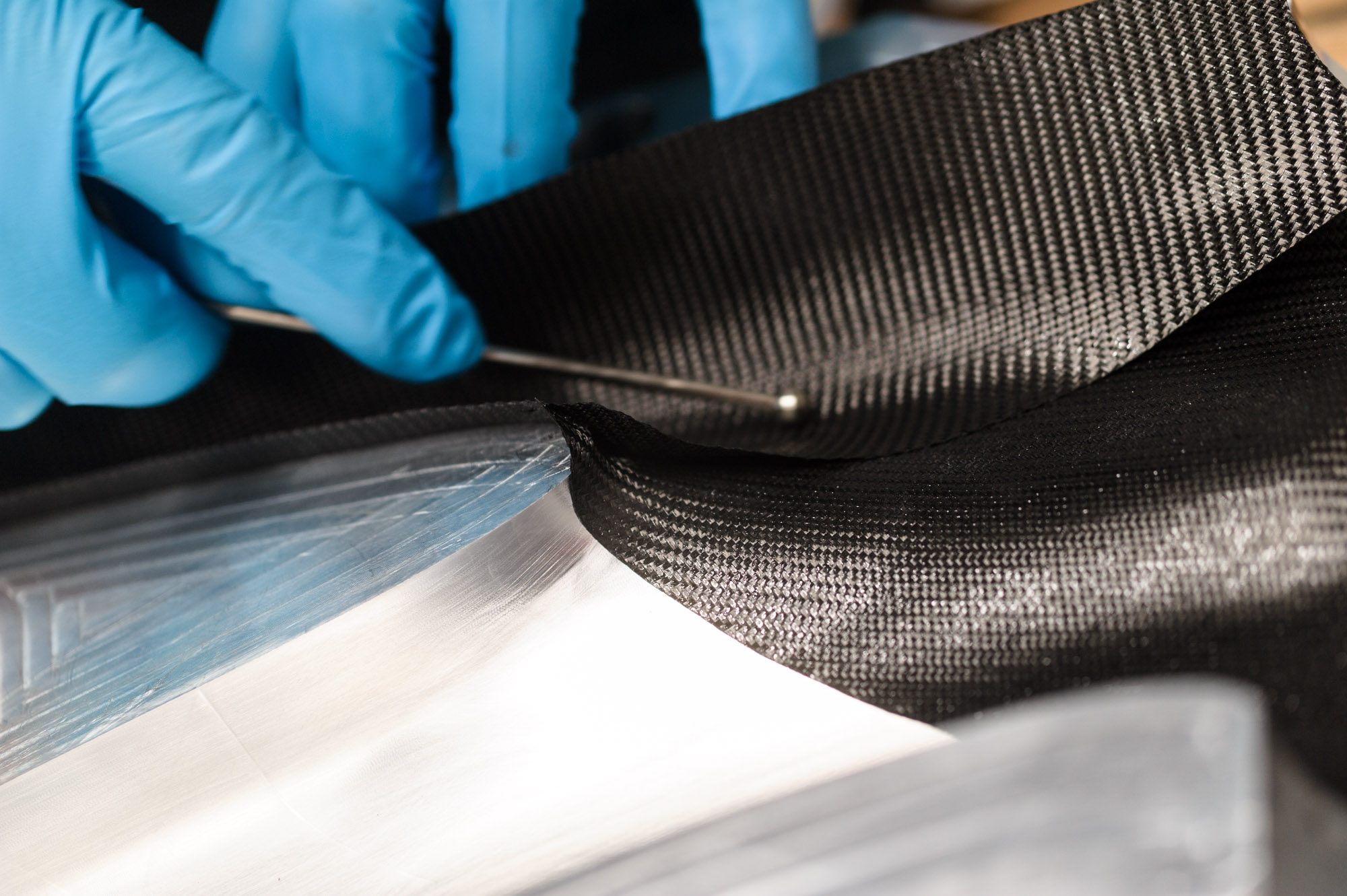

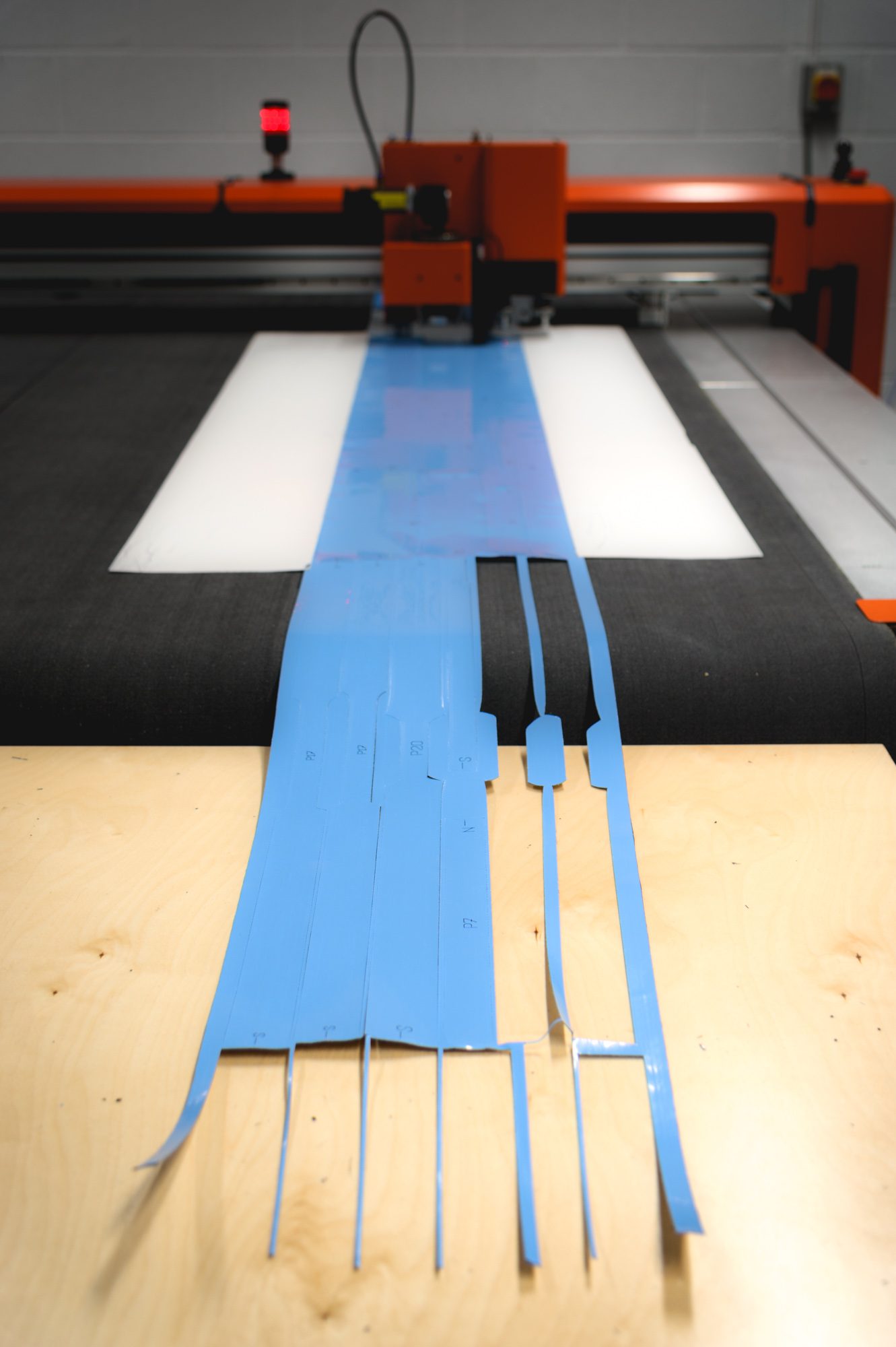

AW – It’s back to that thing of making parts for ourselves and hope to sell a few. Next, Paul (Oldham) will want a proper cross-country bike, possibly, but it’s whether we can make one light enough. Each bike we’re making gets more technical every time and our knowledge base gets bigger and the infrastructure is in place. Instead of one person laying up we’ve got ten who can do it, so prototyping can be done quite quickly. Even if the frame was wrong it’s cheaper for us to machine a new mould than get an aluminium mule welded. We don’t weld, it’s easier for us to lay up a carbon frame now.

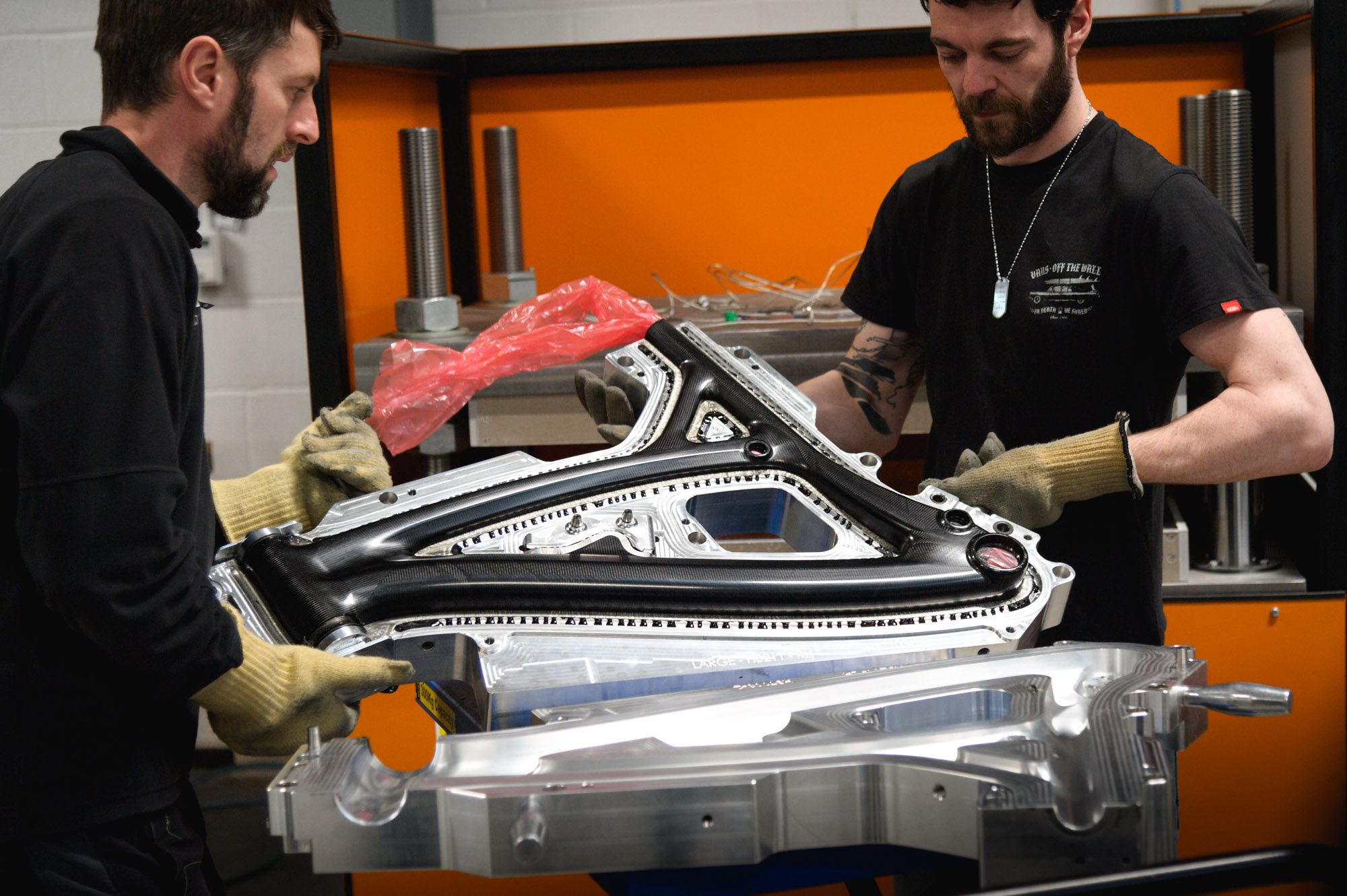

There’s two halves to a mould and it’s a week of CNC’ing for each half. We designed a large HB211 frame just before Christmas and in six weeks we had a finished frame in our hands. So from designing the frame, to working the layups up, designing the mould, machining it, and then moulding the frame was six weeks. If we wanted to change the geometry we could do it tomorrow, it’s just a case of buying the raw material for the mould.

The first frame we ever made, we machined the mould and made the frame in that and the geometry was right the first time. I think because the geometry on the frame is nothing revolutionary, roughly 80% of frames around are the same geometry as ours, it’s just the manufacturing process, the way we’ve made it that’s different.

RW – Normally we’re making components to suit other people’s bikes, but there’s quite a few components that are different on our bike, and that’s been done because Simon [Sharp] always thought that’s the way parts should be, rather than the way we’ve had to make them. The brake, bottom bracket and back-end are bespoke to our frame because we can.

AW – We’re not geared up for mass production, there’ll never be hundreds. We’re going into a niche of a niche market. The only worry is someone will buy one and potentially put it on eBay and sell it for more than they paid. The first few they certainly could, that’s always a worry. Well, not a worry but a shame.

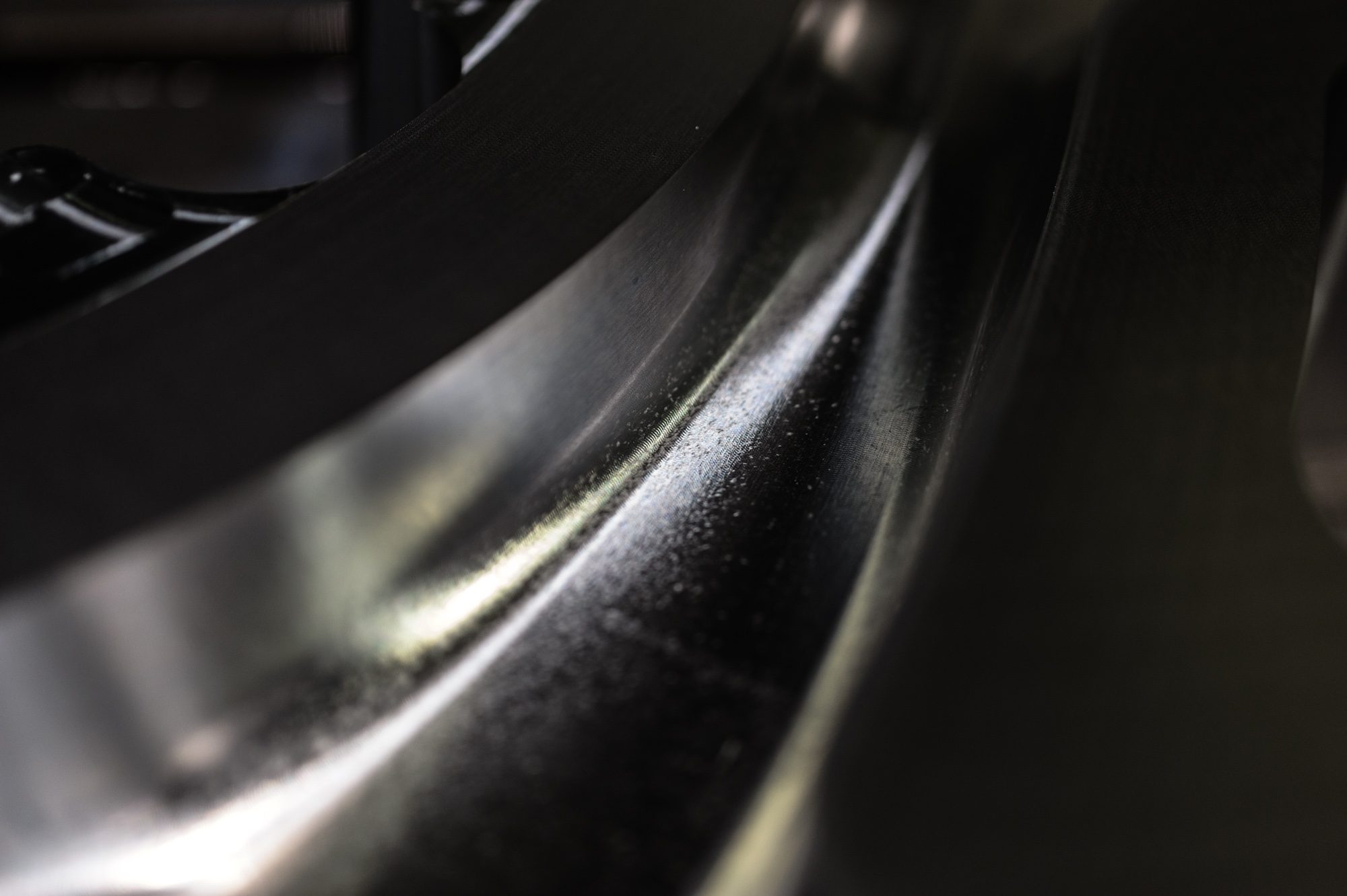

And with that we’re done. Our tour of the factory coincides with the ‘birth’ of a frame. It’s good to see that HB211 number 30 emerges from its mould to receive the shared approval of the workers – drawn in by the spectacle of an event that still retains a sense of something new and wonderful.

It only remains to take Simon out onto the trails. Simon is a key part of the team responsible for milling the aluminium mould, cutting out the carbon sheets, laying up the frame, overseeing the mould in the oven, cracking it out, cleaning it up, adding graphics and laquer and bonding in the pivots on all the HB211 frames. So, it seems right that he’s the one who gets to shred the finished product down some of Hebden Bridge’s finest lines.

It’s still relatively early days for Hope’s new carbon facility and there’s still plenty of space for more machines, moulds and lay up facilities. Given the trajectory of the company’s past we can be pretty sure they’ll soon fill it.

Many thanks to Hope Technology, Alan and Ian Weatherill, Rachael Walker and Simon Perry for their help with this feature.